Slacking Off – Slack and the Corporate Attack Surface Landscape

Published July 22, 2020.

Bottom Line Up Front

- Some media reports stated that last week’s Twitter hack was facilitated by an attacker who fished sensitive credentials from within the company’s internal Slack – essentially leveraging the instant messaging app as a vector for initial access.

- Credentials to over 12,000 Slack workspaces are available for sale on underground cybercrime markets, representing an explicit threat for thousands of organizations. However, examination of both open-source reporting and cybercrime communities don’t reveal a current, well-established attacker interest in the platform.

- KELA assumes cybercrime actors might be having a hard time monetizing Slack compromises since the cloud-based app grants no direct access to a target’s network, and pivoting from it to other internal applications requires a combination of tedious reconnaissance and sheer luck.

- The growth of “big game hunting” tactics in ransomware and the monetization of targeted intrusions lead us to believe that interest in Slack – and other cloud-based apps expanding the corporate attack surface – will probably grow in the future.

- As such, KELA strongly recommends implementing an automated, scalable monitoring solution that offers insights into cybercrime activities targeting cloud-based apps storing sensitive data.

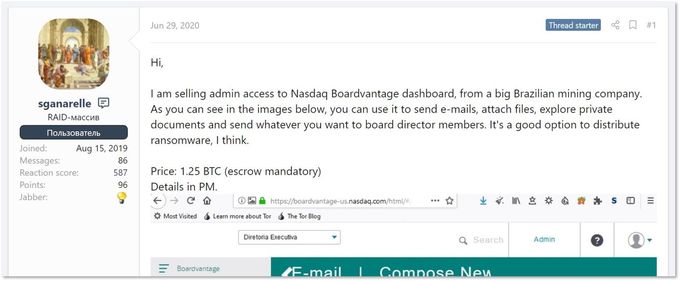

At the end of June 2020, KELA’s research team noted a threat actor, active on a Russian-speaking forum, who posted an ad selling access to a Nasdaq Boardvantage environment used by a Brazilian mining company. The credentials allegedly provide access to sensitive internal materials, and according to the seller can also be used to “distribute ransomware”.

A threat actor’s post on a Russian-speaking cybercrime forum

The apparently-novice actor disclosed too many details demonstrating the breach, and it was picked up by security researchers and shut down. However, the incident highlights threat actors’ interest in gaining access to cloud-based apps used for internal communications and storing corporate data.

Another event demonstrating this trend, although much larger in scale and consequences, is the Twitter hack from last week. The incident is still under investigation, but there is one known fact: the actors gained access to an internal Twitter admin panel that allowed them to manipulate 2FA and recovery settings of user accounts. Security researchers and media outlets have various theories on how the attacker got access: some claim it was an inside job of a bribed employee, others report the actors infiltrated an internal Slack channel, where they found credentials of the admin panel.

These reports present an opportunity to discuss a critical aspect of Slack: the attack surface organizations expose when using the omnipresent instant messaging platform, and how threat actors exploit it.

Much like Boardvantage and other cloud-based apps, the risk involved in using Slack can be hard to quantify; since the platform serves different needs of different stakeholders, it’s hard to incorporate potential compromises into a threat model. Everyone agrees that sensitive credentials shouldn’t be pinned on a Slack channel – until someone forgets and does it anyway. In this context, it makes perfect sense for hacktivists and nation-state actors to be interested in proprietary data available on the platform. But cybercriminals – a major driving force in the commoditization of cyber threats – might struggle to monetize this asset.

Many access types – webshells on online stores, RDP servers or corporate email inbox access – are a highly sought-after resource driving thriving markets; how does Slack fare against them in terms of supply and demand in the cybercrime ecosystem?

The Supply: Abundance of Sensitive Logins Available for Sale

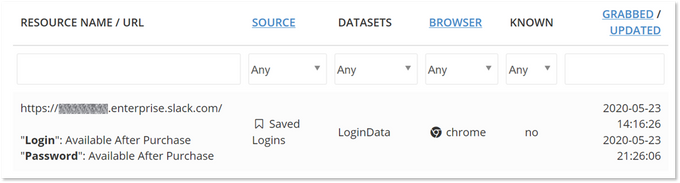

The supply side of the equation is clear: any actor interested in Slack logins can easily find them in automated markets like Genesis Store that sell credentials stolen via infostealers or banking trojans. Querying KELA’s vast databases of credentials offered on these markets, KELA found more than 17,000 Slack credentials offered for sale – starting at $0.50 and going all the way up to $300 per bot.

Credentials for an Enterprise Slack workspace sold on the Genesis Store

Before diving in to the data, let’s quickly explore Slack’s concept of a workspace. After registering, Slack owners at the client-side set up a new environment associated with the organization, defining the context in which users can send direct messages to each other and which channels are visible to them. A workspace is a communal environment where users chat and share information. Workspaces are generated using a unique URL based on the following format:

orgname.slack.com

Making it easy for users to find, join and manage workspaces.

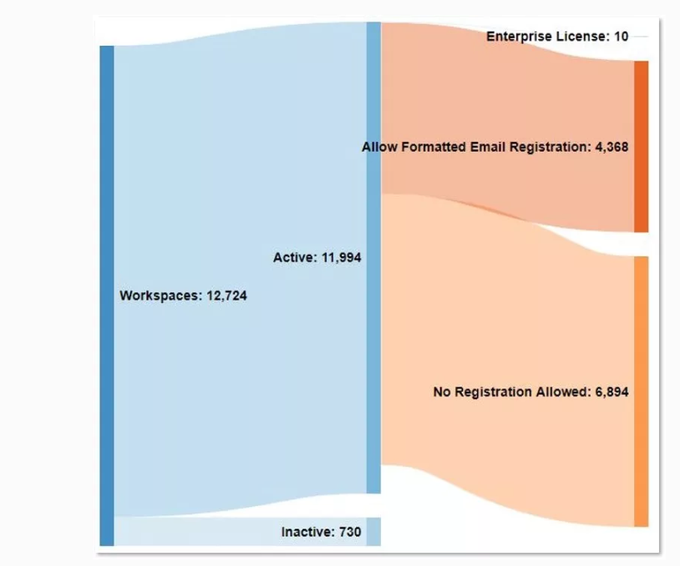

The structured workspace URL proved invaluable when investigating the platform’s exposure on automated cybercriminal markets; after de-duplicating and normalizing the data, we found compromised credentials that offer cybercriminals or other bad actors access to over 12,000 unique workspaces.

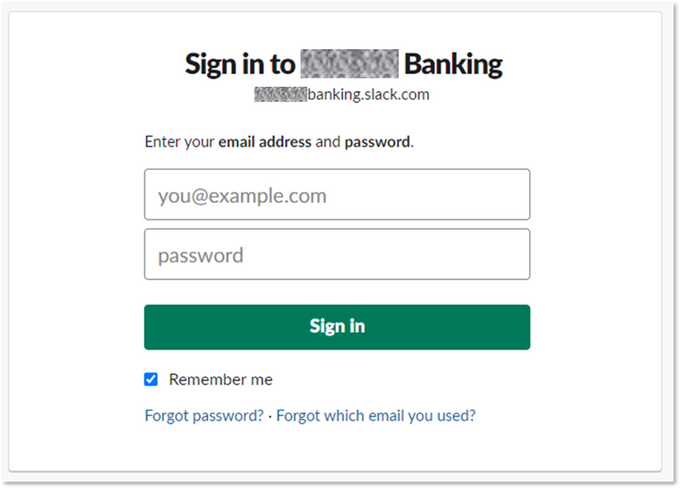

Credentials for the public login panel of this banking service were offered for sale on a cybercriminal market

As anyone can create a Slack workspace for free, the question is, how many of these belong to actual organizations that might be exposed to risk if their compromised credentials were to end up in the wrong hand, and how many are public, community-based workspaces?

To answer that question, KELA scraped the login interfaces of all 12,000 workspaces and analyzed potential indicators of who might use them. We decided to focus on formatted email accounts – a feature that Slack admins can enable, allowing users with emails of a specific domain to register and access the workspace. Already utilized in bug bounties, the premise is that workspaces that allow registration from specific domains are more likely to be associated with organizations. We know this heuristic isn’t free of false positives (or false negatives), but it serves as a better indication of the number of actual internal business workspaces.

One of the thousands of Slack workspace with compromised credentials offered on cybercrime markets. This UI, supposedly of a government entity, allows registrations with formatted email.

Filtering only by workspaces supporting formatted email registration resulted in over 4,300 unique workspaces. As can be seen above, some are government and financial institutions, including banks, insurance companies and more – all have exposed credentials available for purchase in cybercrime markets.

A quick quantitative analysis of Slack workspaces that suffer credentials compromises observed in cybercrime markets

The Demand: Sensitive Corporate Communications or Social Media?

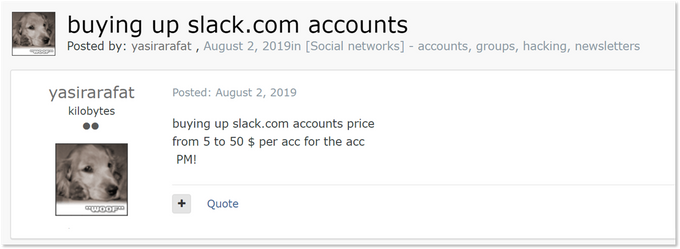

While at least 4,300 organizations seem to have Slack credentials available for sale, the demand side of the equation doesn’t seem to align; browsing cybercriminal forums won’t uncover many threat actors searching for Slack access. One example was a Russian-speaking actor on a top-tier forum, who’s looking to buy Slack accounts:

Almost a year after it was posted, the ad still has no replies. Moreover, we found almost no discussions about schemes or methods to monetize Slack credentials, suggesting there is no active interest in targeting Slack among cybercrime communities.

That same post, though, holds a clue as to why threat actors ignore Slack right now. A careful look at the screenshot reveals the threat actor posted the request in a subforum dedicated to social networks, suggesting the cybercrime community considers Slack as a messaging app, rather than a gateway into corporate platforms and internal data. This is a classic Unknown Unknowns situation where actors might have unprecedented access to sensitive credentials but as a collective, they lack a well-established TTP on how to leverage them for monetary gain.

The Next Frontier

We won’t be generalizing if we say attackers are opportunistic and agile, adapting to new challenges by exploiting the tools at hand. We’ve already seen adversaries – the operators on the SLUB malware – using Slack to enable covert C&C communications. Lately, Red teams and bounty hunters are noticing Slack’s advantages for attackers as vector as well – as seen in write-ups mentioned earlier and in the introduction to Abusing Slack for Offensive Operations by SpecterOps.

So why do malicious actors seem to be slacking (you had to be expecting that pun by now) off when it comes to leveraging Slack as a component in initial access? KELA has a few theories:

- Enumeration: while enumerating a target’s Slack workspace sounds easy enough, it might prove a bit challenging; users can choose the org name listed in the unique URL, and well-utilized obscurity may make it harder for an adversary to identify an opportunity

- Security and identity control: Slack natively supports many SSO providers, making it difficult for an attacker to pivot from/to Slack using compromised credentials. Out of the 12,000 workspaces identified by KELA, several were SSO-only

- Cost-effectiveness: assume you’re an attacker with Slack access; what can you do with it (except for browsing a plethora of memes shared by team members)? You could use it for phishing, which will probably be effective but isn’t as widespread as a good-old spam campaign. You can also obtain sensitive files sent via the chats, but there’s no guaranteed success (though the Twitter hackers definitely nailed it), so gaining access might not be worth the effort

While we found little concrete evidence, we assume APTs focused on espionage or nation-state actors already exploit Slack, since they care less about the three factors mentioned above.

We also assume that the evolution of cybercrime – focusing on servitization and sales automation, as well as increased visibility of goods – will allow cybercriminals to overcome these challenges. Right now, a financially-motivated actor can visit an underground botnet market like Genesis and get an overview of all available corporate Slack logins with two clicks, solving the enumeration problem; once credentials are obtained, Slack’s security (including SSO) can be bypassed using fingerprints sold on the same market – resolving the second issue. These make Slack intrusions cheaper and easier, and – combined with the rise of targeted ransomware, offering new monetization opportunities – may increase their overall ROI, and therefor popularity.

Fortunately, threat intelligence solutions – including KELA’s RaDark and Darkbeast – supply network defenders and threat intelligence practitioners with real-time insights into underground cybercrime activities and the cloud-based attack ecosystem. These can be effectively used to reduce attack surface from Slack and other third-party services, by remediating exposures or taking down compromised data. Specifically, we recommend monitoring not just “classic” network assets – like domains and IP ranges – but also unique URLs and identifiers used on external services, i.e., the organization’s unique Slack URLs.