Defender-in-the-middle: How to reduce damage from info-stealing malware

Victoria Kivilevich, Director of Threat Research

Bottom Line Up Front

- Following recent hacks of Uber and Rockstar Games, KELA decided to take a look at attacks that started with compromised corporate credentials being leaked or traded in the cybercrime ecosystem.

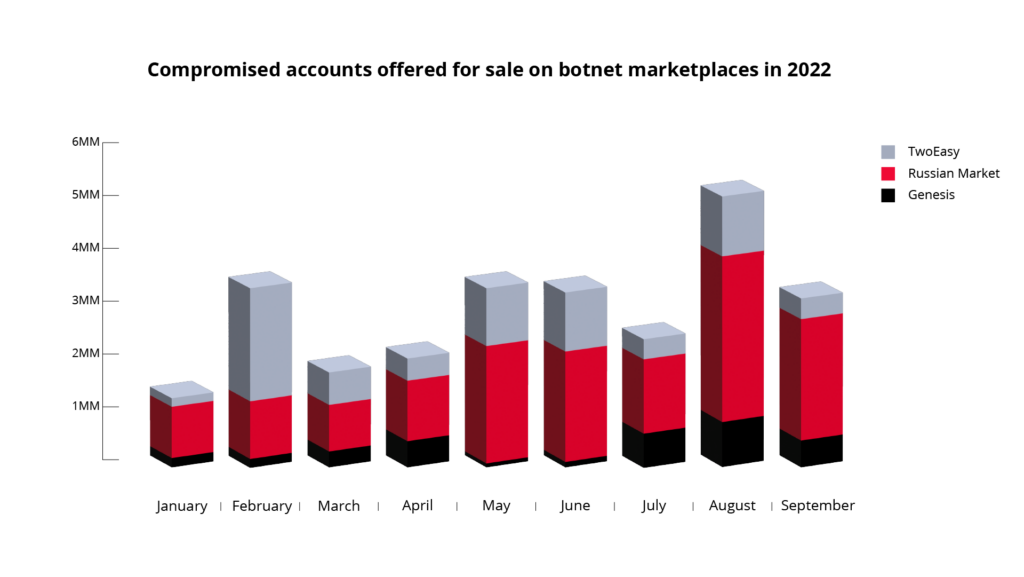

- Nowadays, this ecosystem enables threat actors to easily acquire such credentials that were accessed by information-stealing malware and offered for sale on automated botnet marketplaces, such as Genesis, Russian Market and TwoEasy.

- While some threat actors are looking for banking and e-commerce credentials that they can use to cash out easily by stealing money from a compromised account, smarter attackers target organizations and their corporate credentials. These attackers are exchanging tips for finding such credentials, and they use the cybercrime ecosystem to buy them for a few dollars.

- Luckily, defenders can access the same cybercrime ecosystem and can have the same visibility as a threat actor that is planning an attack. Threat intelligence solutions can be used effectively to monitor exposed assets and reduce attack surface by remediating exposures or taking down compromised data.

- It’s crucial to consider not only direct assets of the company, but also workspaces hosted by third parties, with Slack being a perfect example: based on KELA’s research, thousands of unique workspaces were compromised and could be used for attacks similar to the Electronic Arts incident.

- The evolution of cybercrime — focusing on servitization (paying for a service instead of buying the equipment) and sales automation, as well as increased visibility of goods — will drive more threat actors to use this ecosystem.

When a big-scale cyberattack happens, every security professional on the side of a victim can’t help but ask, “At which point could we stop it?” A decade ago, the answer would have focused mostly on suspicious activity inside a compromised network: what software, what policies and what people failed to detect unauthorized access and malicious activity.

Back then, enterprise defenders had low visibility into the reconnaissance stage of attacks, which includes a threat actor researching a target and gathering information that may help to compromise the company. Threat actors, in their turn, were more used to orchestrate targeted attacks (think of ransomware incidents) from scratch, having less visibility into already-performed opportunistic attacks such as phishing campaigns.

Nowadays, a growing cybercrime ecosystem enables threat actors to obtain and use data gained by other actors, turning one attacker’s trash into another attacker’s treasure. From malware-as-a-service to stolen databases and exposed credit card data an attacker familiar with cybercrime marketplaces and forums can access a variety of services and data with one click and a few dollars. Thus, opportunistic attacks serve as a source for targeted big attacks that end up in media headlines.

Luckily — coming back to the question “At which point could we stop it?” — defenders can access the same cybercrime ecosystem and can have the same visibility as a threat actor that is planning an attack. This access means that they could intervene as “defender-in-the-middle” — in between opportunistic and targeted attacks, with this middle being cybercrime sources.

A skilled and equipped defender can access these markets and forums, find their company’s exposed information and act to prevent further exploitation of this data. To discuss it practically, let’s take a look at the recent attacks that started with a piece of information being leaked or traded in the cybercrime ecosystem, namely, credentials acquired by information-stealing malware, which becomes a popular attack vector.

Setting up the terms

Over the past years, KELA has been looking into innovative and automated illicit markets in the cybercrime underground that sell access to login details, fingerprints and additional data obtained from infected machines. These markets allow their users to search for any wanted resource, browse through a list of infected machines from which credentials to that resource were stolen, and buy the credentials alongside the user’s original web cookies. The best-known markets, which are also called automated botnet marketplaces, include Genesis, Russian Market and TwoEasy (2easy).

The stolen data and browser-saved information (known as “logs”) originate from devices infected by info-stealing malware (referred to as “bots”), such as Redline, Raccoon, Meta and Vidar. If purchased by threat actors, these credentials pose a significant risk to an organization, because they allow actors to access various resources that could result in data exfiltration, lateral movement and malware deployment.

Threat actors using logs as initial vector

Logs, whether obtained by threat actors through their campaigns or bought on markets, have proven to be a valuable source of information for threat actors. However, to find this information, a typical threat actor would need to browse through thousands of stolen credentials and find ones that seem promising. For actors that tend to target the low-hanging fruit, it would be banking and e-commerce credentials that can be used to cash out easily by stealing money from a compromised account. However, smarter attackers have understood for a long time that targeting individuals is not nearly as profitable as coming to organizations (hence the popularity of ransomware operations).

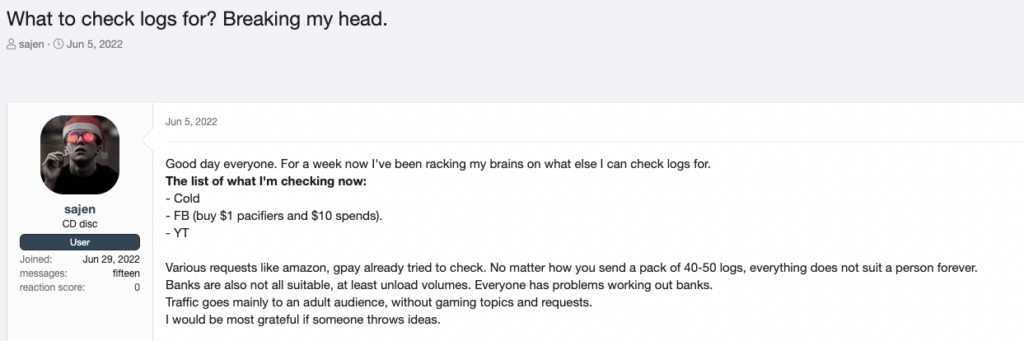

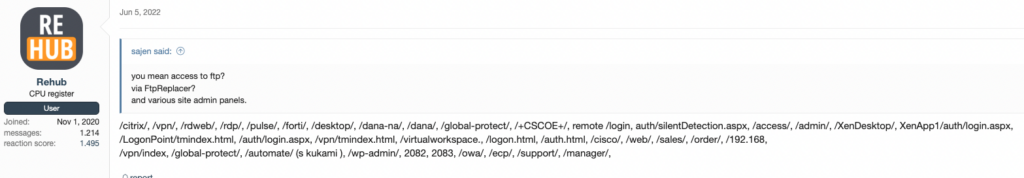

When looking at dark web chatter, one can clearly understand that these actors don’t waste time when searching for such targets. A discussion below shows just one of the multiple threads in which threat actors exchange tips for finding credentials belonging to organizations in logs:

An actor asks what compromised URLs should they look for in their logs (Source: XSS, auto-translated from Russian)

Another actor answers with a list of strings contained in “valuable” URLs (Source: XSS, auto-translated from Russian)

As we can see, the experienced threat actor shares strings contained in URLs that typically would be used by organizations to enable remote access to their network through VPN and RDP. A person familiar with these solutions would see not only known brands (Fortinet, XenApp, GlobalProtect), but also strings specific to some software (“dana” for Pulse Secure SSL VPN or CSCOE for Cisco ASA). Finding credentials to such URLs is valuable for skilled actors since they can use them as an entry point into the organization’s infrastructure. From there, they can continue in any direction they want, including corporate espionage and ransomware attacks.

As the cybercrime ecosystem grows and innovates, more and more actors assist in transforming such opportunistic info-stealer campaigns into targeted “big-game hunting” attacks. For example, Initial Access Brokers, threat actors that sell remote access to corporate networks, are known to research logs in an attempt to find compromised resources of big companies, validate credentials and achieve persistence, and then put access up for sale.

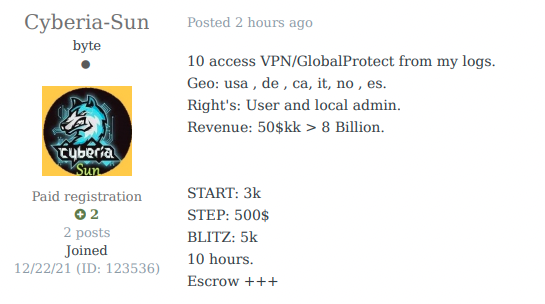

IAB claiming they sell access to companies with revenue from USD 50 million to USD 8 billion — gained through logs.

No matter how big the supply chain becomes, the initial lead stays the same — logs accessed by info-stealers and sold on marketplaces. Review of historical data gathered by KELA shows that compromised credentials to sensitive enterprise systems have been offered for sale on a large scale: for example, more than 11,000 various VPN login pages. These logs could have been intercepted by victims if they were to monitor these markets, and thus the compromised accounts could have been identified and secured.

What happens if they are purchased by cybercriminals? A few recent stories can illustrate that.

Uber

On September 15, 2022, Uber discovered that its network was breached. The attackers were able to access multiple services and internal tools used at Uber, including G-Suite, Slack and the HackerOne admin console.

A threat actor claiming to be behind the attack on Uber shared more information about the attack: they allegedly used social engineering to get access to the organization’s VPN. The attacker had already obtained a valid username and password but needed a text-based, multifactor authentication (MFA) one-time code to be logged in. They performed an MFA fatigue attack against a compromised employee (an external contractor, Uber said), bombarding him with MFA push notifications, and then contacted the employee via WhatsApp pretending to be from the Uber IT team. The attacker claimed that if the employee wanted the notifications to stop, he needed to accept the MFA request; and this is what the employee did.

The initial access vector that allowed the attacker to target Uber could be credentials (logs) that were put up for sale from September 12 to 14 on Russian Market. Apparently purchased by the threat actor, these logs contained authorization information for uber.onelogin[.]com, an identity and access-management provider. These logs indicate that at least two Uber employees from Indonesia and Brazil have been infected by the information-stealing trojans Racoon and Vidar.

In this case, the time frame between when the logs appeared for sale and when they were bought and used in the attack is really short. Therefore, not only timely monitoring could be beneficial, but also established policies of how to react to such threats.

Interestingly, a few days after the Uber incident, an actor called “teapotuberhacker” claimed to have breached Rockstar Games and leaked Grand Theft Auto 6 gameplay videos and source code. The actor said they are responsible for the Uber hack, but it is yet to be confirmed that one actor was indeed behind two incidents.

Uber’s investigation is still ongoing, but the company recently claimed the attack was performed by the notorious hacking group Lapsus$. Many of the group’s attacks are known to involve the use of purchased credentials. It’s possible that the actor used the same TTPs to attack Rockstar Games and will continue to do so.

T-Mobile

In March 2022, Lapsus$ managed to breach T-Mobile and steal source code for various projects and to use the company’s internal tools to conduct SIM-swapping attacks. As discovered based on a copy of the private messages between Lapsus$ members, the attackers continually purchased T-Mobile VPN credentials and tricked employees into adding their devices into the list of machines allowed to authenticate with the company’s VPN.

“I will buy login when on sale, Russians stock it every 3-4 days,” reads one message, indicating that one of the markets Lapsus$ used was Russian Market. Buying compromised accounts on such markets was among the constant TTPs of Lapsus$. Aiming to buy more credentials, Lapsus$ even announced in their Telegram channel that they were interested in obtaining credentials to internet-facing systems and applications VPN, Citrix, AnyDesk, and VDI, or similar access to certain companies that could facilitate their intrusion operations.

Therefore, it can be assumed that the same methods may have been used in some other high-profile attacks by the group, which included incidents in Microsoft, Okta, Nvidia, Samsung and LG Electronics.

In the case of Okta, an identity and access-management company, the environment of a technical support engineer working for the company’s subcontractors is the one that was accessed, through an RDP connection. That gave the attackers access to several high-privilege Okta portals and to information about the Okta clients managed by that engineer. While there is no information on how the RDP credentials to the engineer’s environment were compromised, the modus operandi of Lapsus$ suggests they could try to use botnet marketplaces again.

Electronic Arts

The aforementioned incidents showcase how important it is to proactively monitor a company’s assets on automated botnet marketplaces. When compiling a list of such assets, it’s crucial to consider not only the company’s direct assets, but also workspaces hosted by a third party, such as Slack.

As described by KELA previously, credentials to Slack workspaces are available for sale on various cybercrime underground markets, representing an explicit threat to thousands of organizations. A workspace is a communal environment where users chat and share information. Workspaces are generated using a unique URL based on the following format: orgname.slack.com. That makes it easy for users to find, join and manage workspaces. However, it also makes it easy for threat actors to find compromised Slack accounts on botnet markets.

In June 2021, such easy access made it possible to hack into Electronic Arts. The incident reportedly began with hackers who bought stolen cookies sold online for just $10. The attack continued with hackers using those credentials to gain access to a Slack channel used by EA. Once in the Slack channel, those hackers successfully tricked one of EA’s employees into providing an MFA token, which enabled them to steal multiple source codes for EA games. Interestingly, at least one member of Lapsus$ was part of this attack, according to dark web chatter observed by KELA.

The risk involved in using Slack can be hard to quantify. Because the platform serves different needs of different stakeholders, it’s hard to incorporate potential compromises into a threat model. A lucky threat actor doesn’t even need to social engineer their victims if the company’s employees rely on Slack for saving sensitive information, which happens pretty often. KELA assumes that interest in Slack, and other cloud-based apps that expand the corporate attack surface, will probably grow.

For context, currently, KELA’s platforms indexed more than 67,000 compromised Slack URLs, which means that thousands of unique workspaces were affected. In relation to other workspaces hosted by third parties, more than 10,000 compromised URLs pertain to companies’ sign-in pages to Okta. Any other third-party solution — you name it — is most likely exposed on botnet markets as well.

Conclusion

KELA assumes that the evolution of cybercrime — focusing on servitization and sales automation, as well as increased visibility of goods — will drive more threat actors to use this ecosystem. In particular, a well-established system for trading logs makes it easier for threat actors to gain access and scale their attacks. This supply chain will only strengthen in light of the unfading popularity of information stealers offered as malware-as-a-service.

Fortunately, threat intelligence solutions, including KELA’s platforms, supply network defenders and threat intelligence practitioners with real-time insights into underground cybercrime activities. These insights can be used effectively to monitor exposed assets and other third-party services and reduce attack surface by remediating exposures or taking down compromised data.

Specifically, we recommend monitoring not just “classic” network assets like domains and IP ranges, but also unique URLs and identifiers used on external services, for example, the organization’s unique Slack URLs.

ACCESS KELA’S PLATFORM FOR FREE TO AUTOMATICALLY EXPOSE RISKS TO YOUR ORGANIZATION